Monday, March 25, 2019

'Eleanor Oliphant is completely fine' by Gail Honeyman

No one’s ever told Eleanor that life should be better than fine.

Meet Eleanor Oliphant: She struggles with appropriate social skills and tends to say exactly what she’s thinking. Nothing is missing in her carefully timetabled life of avoiding social interactions, where weekends are punctuated by frozen pizza, vodka, and phone chats with Mummy.

But everything changes when Eleanor meets Raymond, the bumbling and deeply unhygienic IT guy from her office. When she and Raymond together save Sammy, an elderly gentleman who has fallen on the sidewalk, the three become the kinds of friends who rescue one another from the lives of isolation they have each been living. And it is Raymond’s big heart that will ultimately help Eleanor find the way to repair her own profoundly damaged one.

MY THOUGHTS:

The title didn't grab me when I first saw it. I thought, 'Eleanor's obviously not fine at all,' and walked past. Since then, it's become a phenomenon, with must-read recommendations from all sorts of people. When I saw it at a bargain bookshop, I thought I'd take my chance. I had two false starts, finding it hard to muster the interest to get beyond a bikini wax appointment at the start. But even more readers kept the glowing reviews coming, and rumours of a movie are in the pipelines. So I pushed through and finished the book at last. It's all about lonely Eleanor with a horrific past she's trained herself never to think about, and Raymond, the friendly IT guy who takes a genuine interest in her, making him the very first.

Other workmates have largely ignored her because Eleanor's not easy to warm up to. She's been totally alienated for a good two thirds of her life, which hasn't been great for her social skills. She's sharp, observant and tends to make outrageously tactless statements, partly because solitude hasn't given her empathy muscle much room to develop, and partly because not having rubbed shoulders with others, she simply hasn't picked up socially acceptable responses.

I share the love for the features other readers rave about. It's great that a doughy, paunchy, super-scruffy IT worker like Raymond is shown to be the hero his kind heart makes him. This guy deserves to wear a cape. I like the revelation that small, simple deeds we may not even bother offering could actually be what makes the world go round. I like Eleanor's growing appreciation for Raymond, who she dismisses as a bore and a slob at first. And what I love most is seeing how success and progress for Eleanor means returning bravely to the life she was already living. It's so true that often what's required isn't worldly accolades, material goods, or change of circumstances, but simply a fresh outlook. We don't need to make a splash or public stir of any kind to be worthwhile human beings.

With all these excellent qualities, I was still a bit ambivalent when I finished. I loved the end, but for the first two thirds, I wasn't driven to pick up the book. I think it's because of what I'd call a broken record quality. There's a predictable repetitiveness, when a basic episode keeps recurring in slightly different circumstances. A huge chunk of the book is full of incidents that fit into either of these two categories.

1) Eleanor goes for some beautifying, pampering or retail therapy. The stranger behind the counter reacts with the rolling of eyes, or some other sign to show that she comes across as an eccentric. Or 2) She is out at some lunch, party or social event, and makes a tactless comment that proves she's unaware of social conventions. Raymond almost chokes on whatever he's messily chewing, stunned yet again by her frankness or naivety, until he recollects himself and things start rolling again.

The story's bestseller momentum is speeding faster than its glacial plot. So many thousands of readers have taken lonely, weird Eleanor to their hearts, I wonder if that love is extending to the real-life oddballs in their own offices and schools. Or are these solitary bods still sidelined and overlooked while their acquaintances are standing around, raving on about their compassion for Eleanor Oliphant? If it truly does open people's eyes to the invisible mass of traumatised and depressed folk around us, and inspire us to take on Raymond's simple mission, it'll be worth every cent spent.

But maybe it's not entirely about others at all, but more about us. Maybe we warm so readily to Eleanor because she displays many of our own secret personal doubts. (Minus her lack of close family members and horrific background.) Do we relate to her impression of being a perpetual fifth wheel in the world, unnecessary and unappreciated? Or her floundering feeling of not quite grasping the social cues that link everyone else? Or her empty yearning when she scrolls down the social media of others? Or foolish, personal histories of getting carried away on waves of imaginary saviours and rosy futures? I can raise my hand to all of these, at different moments. If the story helps us be easier on ourselves, it's worth every cent spent too.

Some of the healing things that help Eleanor start to live again, when she's faced her traumatic past, include simple fixes that can do anyone good. 'Noticing detail, that was good. Tiny slivers of life added up, and helped you feel that you too could be a fragment. When you start to notice things around you, you feel lighter.' There's one for any of us who find ourselves in an intense fog of preoccupation.

Being a skillful helper like Eleanor's psychologist Maria Temple may be far from reality for many of us, but maybe we could at least aspire to be like Raymond (although he is amazing in pushing through with somebody whose manner isn't particularly warm.) Or we could be like his mother Betty, who Eleanor calls 'quite simply a nice lady who raised a family and now lives quietly with her cats and grows vegetables. That is both nothing and everything.' Or Sammy, the loving old dad whose friendliness extends to his rescuers.

I don't want to give the idea that nothing but random acts of kindness ever happen. There's a poignant subplot where Eleanor allows herself to form pipe dreams about a random, handsome face, and also a plot twist I'm not entirely convinced came off flawlessly. This is one of those times I wish I could discuss spoilers. Let's just say it puts Eleanor Oliphant up there with the biggest unreliable narrators of all time, but that's enough. Overall, I'd give the book four or five stars for the theme and the ending, but just one or two for the tortoise pacing throughout the start. It's one of those cases where I have to take the averages for my final ranking.

🌟🌟🌟

Tuesday, March 19, 2019

'The Help' by Kathryn Stockett

Be prepared to meet three unforgettable women:

Twenty-two-year-old Skeeter has just returned home after graduating from Ole Miss. She may have a degree, but it is 1962, Mississippi, and her mother will not be happy till Skeeter has a ring on her finger. Aibileen is a black maid, a wise, regal woman raising her seventeenth white child. Something has shifted inside her after the loss of her own son, who died while his bosses looked the other way. Minny, Aibileen’s is short, fat, and perhaps the sassiest woman in Mississippi. She can cook like nobody’s business, but can’t mind her tongue, so she’s lost yet another job.

Seemingly as different from one another as can be, these women will nonetheless come together for a clandestine project that will put them all at risk. And why? Because they are suffocating within the lines that define their town and their times. And sometimes lines are made to be crossed.

MY THOUGHTS:

I'm late on this book's bandwagon, but bought a copy from a second hand shop and finally got around to reading it. I get anxious about starting books with themes of racism. There's bound to be deep sadness, and in our current era of strict political correctness, do these stories even apply the balm of kindness we all need, or simply act as a match to a highly charged tinder box? There's no point trying to heal a deep wound by always picking at the scars. So I was nervous going in, but it turns out I needn't have been. There's a lot to love about this To Kill a Mockingbird/Upstairs Downstairs hybrid. It's all about being a good and decent person.

The story is set in Jackson, Mississippi in the early 1960's, when racial discrimination was still as ugly as ever. It seemed the only real job prospect for a coloured woman was a maid and cleaner, and there were many white women demanding their service. 'The help' would basically bring up the children of their snooty employers, who then wondered why their kids preferred the hired people. Most folk accepted the status quo, until a trio of women rocked the boat with a top secret assignment, proving that the written word can pack a powerful punch.

White girl Eugenia (Skeeter) Phelan is upset when her beloved family maid Constantine is fired while she's away at college. It prompts her to consider writing a book full of interviews with coloured maids, but it's hard to find any takers for such a subversive act. Especially because coloured people are automatically suspicious when white folk are nice to them, with good reason. But eventually she gets Aibileen and Minny on board, who have been pushed far enough to realise that the time is ripe for speaking up.

These three narrators switch frequently throughout the story, and it's done so well that that when each one ends, we shake our heads moving on to the next, but are soon hooked by that thread too. It's all about cleaning and childcare of course, but has suspense and mystery. Why must Minny hide her presence from her boss's husband? What was the big surprise Constantine had in store for Skeeter, which she never discovered? Will Aibileen ever be caught when she tries to build up the confidence of Mae Mobley, the little daughter of her employers?

Skeeter becomes one of those self-sacrificial writers who are called to put everything on the line, although she never sets out to be. Her bright idea begins as nothing more than a brainwave to help further her own career prospects. Yet it soon becomes evident to her that pursuing it might mean losing everything else important to her. Such a lot is stripped away that her only reason to continue has to be belief in the cause itself. For her more than anyone else, it's very much a personal growth story.

Minny's part of the story is very cool. She's one of the most indignant and wronged people of all, but finds herself disarmed by her new employers, Celia and Johnny Foote, who don't fit into the pattern she's grown to expect from white people.

The villain of the piece is Hilly Holbrook, a young trendsetter who many other white ladies look to for cues as to how to think and behave. She's trouble on two legs; in a perfect position to use her social power for kindness, but choosing prejudice and meanness instead. Minny says that Hilly is sent by the devil to ruin lives. She's the sort of nasty girl who seems sweet on the surface, but spells disaster for anyone who crosses her. It's fun for readers to hate Hilly, and speculate who she'll push too far.

My favourite character, who provides the overall tone of kindness and love, is Aibileen. I'd love to be on her prayer list! They have a proven track record. She always writes them instead of speaking them, because a teacher once challenged her to keep reading and writing every day. Her own faith surely adds to their power, since she considers them to be like electricity that keeps things going. That's why she carefully considers whether it's worth the risk of adding any new folk, like Miss Skeeter. And Minny adds, 'We all on a party line to God, but you sitting right in his ear.' What a wonderful inspiration for all of us readers to think of prayer the same way, and that might be one of the best takeaways from the whole book.

🌟🌟🌟🌟½

Friday, March 15, 2019

The World's Greatest Narcissists

Narcissism has always been a human problem throughout the ages, but it's easier than ever to indulge in the 21st century, because we have so many outlets to toot our own horns. Our potential audience is not just neighbours in our close vicinity but people from all around the globe. Arguably, the wonders of social media give our narcissism cultural validation. The 1970s was called the 'Me Decade', and now there are claims that we've simply moved a step further to the 'iEra'. Christopher Lasch, in 'The Culture of Narcissism' suggests that it's simply the characteristic pattern of our culture. Ouch, I don't want to be swept along by that tide, but in our day and age, it's all too easy.

Several people have suggested that we just stop. Not only because it's a bad habit, but it makes us so miserable. They advise us not to check our social media updates often, or spend obsessive time on impression management, and if we're feeling unduly depressed, we should examine our hearts to determine whether or not it's simply because our brilliant post hasn't received as many likes, hearts, or shares as we'd hoped for (ouch again).

I believe going cold turkey is easier said than done. But maybe this list of mine could be an added tool to scare us out of our narcissistic habits, for who wants to see ourselves mirrored in these dudes? I'm calling them the greatest narcissists, but hey, they would call themselves the greatest, full stop.

1) Narcissus

Since he provided the name, I'll kick off with this haughty and gorgeous young man from Greek mythology. He's lured to the side of a pool, where he beholds his own reflection and falls deeply in love with it. Not realising it's merely his own image, he's unwilling to leave, and eventually pines away, believing his love is not reciprocated. Hence, the term 'narcissism' was coined for people who have a fixation with themselves, their appearance and public perceptions.

2) Lucifer

He was hailed as the most beautiful angel of all, the bright morning star. But this wasn't enough for him. His enormous ego and thirst for adulation led him to challenge God's position. Whoa, that's some serious narcissism.

3) Dorian Grey

This young man is the (anti)hero of Oscar Wilde's masterpiece. His initial reaction when his portrait is unveiled is heartache because he won't stay so gorgeous. He vows to give his soul if only he can keep his wonderful beauty while the portrait grows old and faded instead. (My review is here.)

4) Gaston

Belle's persistent suitor won't take no for an answer, because he truly believes he's too wonderful to resist for long. The hordes of village admirers do nothing to quench his vanity. In the movie, we see him saying, 'You are the most gorgeous thing I've ever seen,' and the scene pans out to show that rather than addressing Belle, he's standing before a mirror. He's prepared to take her by force toward the end, just because he can't stand the idea that she isn't head over heels in love with him, as every other girl seems to be. And whatever Gaston wants, Gaston gets, until now.

Belle's persistent suitor won't take no for an answer, because he truly believes he's too wonderful to resist for long. The hordes of village admirers do nothing to quench his vanity. In the movie, we see him saying, 'You are the most gorgeous thing I've ever seen,' and the scene pans out to show that rather than addressing Belle, he's standing before a mirror. He's prepared to take her by force toward the end, just because he can't stand the idea that she isn't head over heels in love with him, as every other girl seems to be. And whatever Gaston wants, Gaston gets, until now.5) King Saul

A biblical narcissist, he was Israel's first king. Saul started off okay, but succumbed to a deep need for everyone to call him the best, before he could relax. He built monuments in his own honour, and when he heard snatches of song that David was admired even more than he for his war conquests, he couldn't stand it. He set out to murder the perceived threat to his position on several occasions.

6) Snow White's stepmother

6) Snow White's stepmotherIn a way, she was the female counterpart to King Saul. She had to stand before her magic mirror to reinforce that she was the fairest in the land before she allowed herself to get on with her day. And it was all for her personal glory. One day when she learns that another person is fairer, she sets off in a rage to have her killed, because being the second fairest in the land would be a disaster. Although she's the only female on this list, I'm sure there are as many girl narcissists as boys out there for real.

7) Bree

There's no reason why they all have to be human, either. C.S. Lewis gave us a very narcissistic horse. Bree was always anxious to make sure everyone was aware that he was a noble, Narnian war stallion, and not a common stable hack. The thought that rolling on his back might be a vulgar Calormene habit he's picked up horrifies him. He's always clear that he's the boss of the mission, and the spurs and reins are just for show. Toward the end, he's humbled and chastised when circumstances prove that he's not the brave, perfect steed he thinks he is. And as Aslan says, it makes him a much nicer horse.

There's no reason why they all have to be human, either. C.S. Lewis gave us a very narcissistic horse. Bree was always anxious to make sure everyone was aware that he was a noble, Narnian war stallion, and not a common stable hack. The thought that rolling on his back might be a vulgar Calormene habit he's picked up horrifies him. He's always clear that he's the boss of the mission, and the spurs and reins are just for show. Toward the end, he's humbled and chastised when circumstances prove that he's not the brave, perfect steed he thinks he is. And as Aslan says, it makes him a much nicer horse.8) Emperor Kuzco

Another animal, he's a llama throughout much of the story, although he starts off as a very spoiled, human brat. Even in his miserable transformed state, he keeps wanting to see the spotlight moved from the good-hearted Pacha back to himself, because he's the star! He's the teenage monarch who was prepared to demolish an entire peasant village to build himself a theme park in his own honour. Thankfully, he's young enough for some decent character development throughout the movie, where he learns empathy for others, in the nick of time.

9) Prince Hapi

While we're mentioning rulers, this one was played by Arnold Schwarzenegger in the 2004 movie version of Around the World in 80 Days. Clearly used to moving people as chess pieces, the prince demands that the trio of main characters come to his banquet, then insists on keeping the lovely Monique La Roche to join his harem. Their only way of enforcing her release is to threaten harm to the precious statue of himself, cast in the guise of the Thinker. It's well worth a watch.

10) Zap Brannigan

He shows that narcissism will be alive and well in the future. The general public think he's a respected military hero, but his crew know him to be an arrogant and incompetent narcissist who will sacrifice them at the blink of an eye. He expends a lot of energy trying to foster his heroic illusion, and win the heart of Leela, whose one eye sees through him clearly enough.

He shows that narcissism will be alive and well in the future. The general public think he's a respected military hero, but his crew know him to be an arrogant and incompetent narcissist who will sacrifice them at the blink of an eye. He expends a lot of energy trying to foster his heroic illusion, and win the heart of Leela, whose one eye sees through him clearly enough.11) Caul

Without giving away too much of his role in the Peculiar Children series, the considerable effort he expends to rise to the top is all for his own personal glory. He's easily seduced by imagining himself in history books of the future, and is known to stop what is happening, so he can make lofty quotes and speeches for that purpose. (My reviews of the series begins here.)

12) Napoleon

I'm including the version of the mighty French emperor portrayed by Count Leo Tolstoy in War and Peace. It may be somewhat skewed, since Tolstoy was clearly on the Russian side of the war in his masterpiece. However, I'm sure he loved writing the narcissistic quirks of Bonaparte, including his passion for positive feedback and careful impression management for future history books. The fact that one man's drive to conquer Europe resulted in the deaths of millions is a dark side of narcissism that deserves to be highlighted. (My review of War and Peace is coming soon.)

And my favourite Narcissist

13) Gilderoy Lockhart

He's the Defence Against the Dark Arts teacher in Harry's second year at Hogwarts, who we first meet on a book tour for his autobiography, Magical Me. At that stage he comes across as an insufferable celebrity who has let fame go to his head. When Harry is placed in detention, Gilderoy's punishment is to get him to write replies to his extensive fan mail. He soon reveals himself to be more incompetent than his heroic memoirs and text books would have people believe. And at last, he's unveiled as a crook who has destroyed the real heroes, just to claim their glory for himself. He's prepared to blast Harry's and Ron's memories, not because he has anything against the boys, but because they know his shameful secret. What a guy!

A funny, but sort of sobering list. They're famous alright, but I doubt any of them would have wanted to be famous for being narcissists. As always, I'd enjoy reading your thoughts, not to mention any extra narcissists I may have missed.

Monday, March 11, 2019

'The Magic Pudding' by Norman Lindsay

The adventures of those splendid fellows Bunyip Bluegum, Bill Barnacle and Sam Sawnoff, the penguin bold, and of course their amazing, everlasting and very cantankerous Puddin'.

MY THOUGHTS:

This kids' classic is a bit like an Aussie version of The Wind in the Willows, and it's my choice for the Africa, Asia or Oceania section of the 2019 Back to the Classics Challenge. It was published in 1918, the year of my grandmother's birth. Bunyip Bluegum is a fashionable young koala who sets out to be a gentleman of leisure, until he gets too hungry. He befriends Barnacle Bill the sailor, and Sam Sawnoff the penguin, who own a magnificent pudding named Albert, with the ability to replenish himself so they need never go hungry again.

Albert is a 'cut and come again' pudding, who enjoys offering slices of himself to everyone. For a change of flavour, you whistle twice and turn his basin around. I read one reviewer's complaint that you only ever seem to get steak and kidney, jam roly-poly, apple dumpling or plum duff. My instant thought was, 'Heck, what does she expect from a pudding?' That lady strikes me as a reader with no sense of wonder. He sounds pretty super-duper and worth the fuss to me.

The nefarious pudding thieves, Possum and Wombat agree, and concoct all sorts of sneaky mischief to steal Albert. Then the trio has to be just as crafty in getting him back again. There's a lot of punching and name calling, which probably delighted the good little children of early last century.

Talking about the target audience, it has some very mature concepts and expressions for a kids' book. For example, the wordy Bunyip Bluegum defends the truthfulness of his poetry with this line. 'The exigencies of rhyme may stand excused from a too strict insistence on verisimilitude, so that the general gaiety is thereby promoted.' Wow, I think several adults would have trouble getting their heads around that one, let alone middle school students. I'd love to think 9 to 12 year-olds would be willing to nut it out with their dictionaries, but do you think it's likely from our 21st century bunch? Are books like The Magic Pudding handy tools to stretch our kids' minds, or just relics from the past still being foisted on a generation no longer in the same head space? We'd never find such tricky sentences in modern stories for the same age group, but I wish a few would slip through, just to see how it would go over.

I think some of the low-key attitude take-aways were the coolest feature of this story.

Bill is easily brought to the brink of despair several times, which makes it harder for his mind to latch onto problem solving solutions. But Bunyip's more optimistic nature makes him a more pro-active thinker, and he often saves the day. It's interesting to see an author from as far back as Norman Lindsay suggest to young readers that choosing our moods may help us switch on or off our creativity.

Albert is a cranky pudding with a sassy mouth, but the friends are willing to cop a bit of guff from him, considering the benefits he provides. He's my favourite character. I love his wise little wrinkled face. He strikes me as a chap who knows full well that people are just using him for what they can get. Even when the pudding owners consider that they've 'saved his life', it's all a matter of indifference to him. He seems just as content with Possum and Wombat, who are after all doing just what the trio of heroes do, which is eating him.

It's such a silly tale, but Norman Lindsay's illustrations, fantastic verse, and emphasis on the chilled, laid-back aspects of Australian life give it its special edge. There's plenty of relaxing over pudding slices and billy tea. 'If you don't sit by a campfire in the evening, you have to sit by nothing in the dark, which is a most unsociable way of spending your time.' Then morning turns out to have its own unique charm. 'It's the best part of the day, because the world has had his face washed, and the air smells like Pears soap.'

The little band's chosen lifestyle is wandering along roads, indulging in conversation, song and story. And their happy ending is removing to a secluded spot and settling down to a life of gaiety, dance and song. Sounds pretty good to me.

The ending is odd by today's standards. The cast give no indication all through the story that they know they are fictional characters, but then Norman Lindsay has his main duo finish this way. (Totally in character for both of them, I might add.)

Bill: Here we are close to the end of the book, and something will have to be done in a tremendous hurry or else we'll be cut off short by the cover.

Bunyip: The solution is perfectly simple. We have merely to stop wandering along the road, and the story will stop wandering through the book.

What do you think? Touch of brilliance or verging in the realm of too cute? Every reader will have to make up their own mind. I can honestly see both sides.

(The photo of me with the Magic Pudding gang was taken at the Story Book Trail at Aberfoyle Park, not far from home; a walk I recommend if you can.)

🌟🌟🌟

Monday, March 4, 2019

Characters who refuse to take responsibility

Okay, when you think of the stereotypical story, who is the hero's direct opposite? If you're like many including me, your reflexive answer may be, 'The villain.' It stands to reason that there's black and white, good and evil. That's why we have the likes of Voldemort, Emperor Palpatine, Captain Hook, Joker, the Wicked Witch of the West, and ultimately Satan, who is actually a character in Milton's Paradise Lost.

But not all stories are written with such obvious play-offs between good and evil, or such desperate stakes. It seems when I think about it, that in other, more low key stories, the good protagonist has another direct opposite. He's not the bad guy, but simply the fellow who can't be bothered. In these stories, apathy is presented as the opposite to caring. The heroes are good-intentioned men who are pro-active in improving their worlds. But then there's the man who prefers to flee, shrink away, or hide his heads in the sand like the proverbial ostrich. He's most expert at shirking personal responsibility, and here is my count down of examples.

Keep in mind, owing to the nature of these lists, there'll be a few plot spoilers.

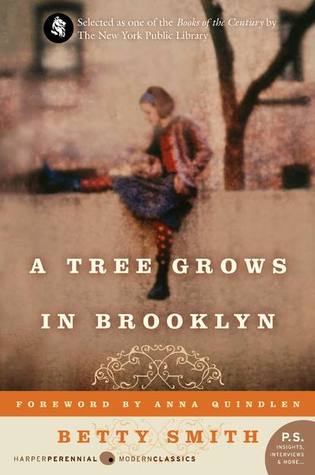

Johnny Nolan

Johnny NolanHe's a good-natured singing waiter who loves his little drink, but taking care of his young family is something he just can't step up to do. His wife Katie is the family breadwinner. It dawns on her early on, with two helpless babies, that if they rely on Johnny they'll starve. Her cleaning jobs become their lifeline. (See my review of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn)

Fred Vincy

This young Victorian man has no idea what to turn his hand to. He'd prefer to keep sponging off his parents forever than choosing a profession. But some of his money-wasting, reckless pastimes cause heartache to the girl he loves. Fred's theme in Middlemarch is realising that he has to step up and just choose something. He's one of the rare success stories from my list. (See my review of Middlemarch)

Godfrey Cass

Godfrey CassThe squire's wishy-washy son once had an unfortunate fling with a poor village girl who died. When he discovers his anonymous baby daughter is destitute, he's not going to step forward and admit ownership. It'd ruin everything, especially his relationship with the elegant Nancy, who he hopes to marry. Staying silent while an old, eccentric weaver volunteers to bring up his daughter is by far the easiest action (or non). But circumstances make Godfrey regret it years down the track. (I love the line where his dad tells him, 'You hardly know your own mind well enough to make both your legs walk one way.') See my review of Silas Marner)

Stepan Oblonsky

Anna Karenina's smarmy brother has a plum government job and a disarming way of making everyone think he's a charming guy. He loves his affairs with multiple women, and always blocks out whatever he can't be bothered with, including his wife Dolly and their young children. But Stepan knows his good friend Levin is always around to pick up the slack and look out for their needs, which is just fine with him. (See my review of Anna Karenina)

Piers Aubrey

He's the unstable dad from Rebecca West's The Fountain Overflows. Piers keeps his family in a constant state of near starvation, because his entire focus is on the unpopular causes he chooses to support. He'll even take from the meager stores his family have, and gamble away furniture and other belongings. Eventually he walks out on them without warning. Luckily, his wife kept the value of a few heirlooms top secret, just because she knew him so well. (See my review of The Fountain Overflows)

James Mortmain

His first book was a brilliant hit, but he's suffered from writer's block and self-pity ever since, while his children have grown up cold and hungry. The kids figure out that fending for themselves is a wiser action than waiting for their father to come through with a new book. Until one day, Cassandra and Thomas decide to take matters in their own hands and force him to get words down on pages. (See my review of I Capture the Castle)

Philip Curtius

The talented, but undeniably wimpy wax sculptor takes the very young Madame Tussaud (Marie Grosholtz) under his wing. But he doesn't have the gumption to stick up for her when she's treated harshly by his business partner, the widow Picot. (See my review of Little)

Captain Ahab

The crusty old peg-legged sea captain of the Pequod is so intent on his revenge mission to destroy the whale Moby Dick that he'll jeopardise the safety of his whole crew to achieve it. Irresponsible and stark crazy make a bad combination, especially when you're the boss of the whole voyage. (See my review of Moby Dick)

Victor Frankenstein

Victor Frankenstein This young science student turns his back on his own creation, who is helpless and clueless at that stage. And the only reason is because of how he looks. As soon as he sees his project animated, Victor panics and flees, hoping it'll just disappear. His refusal to take responsibility helps make him and the monster equal hero/villains, which is why I consider this the most interesting example. (See my review of Frankenstein)

Running my eyes down the list, the most disturbing trend is that the majority of these guys are fathers or in a fatherhood role. That includes Frankenstein as creator. It wasn't my intention when I started, but surprises me in retrospect. The fact that I've drawn this list from a wide range of sources and time periods speaks volumes, considering the emasculation of dads that frequently occurs in our modern media. It seems the sorry stereotype of the clueless, useless moron who sits around while his wife pulls everything together has generations of fuel from which to draw. Perhaps we should take it as a sign that the world has always cried out for solid, dependable, sturdy and reliable family men who'll take a stand and be rocks instead of jellyfish. Let's keep looking out for real life heroes and applauding them when they come.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)