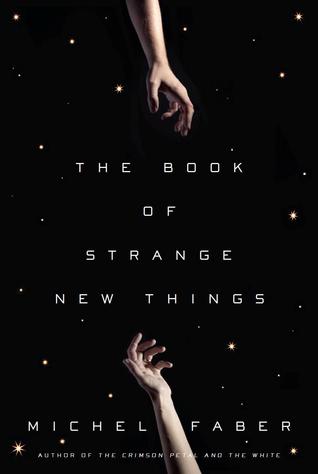

Sophisticated, witty, and ingeniously convincing, Susanna Clarke's magisterial novel weaves magic into a flawlessly detailed vision of historical England. She has created a world so thoroughly enchanting that eight hundred pages leave readers longing for more.

English magicians were once the wonder of the known world, with fairy servants at their beck and call; they could command winds, mountains, and woods. But by the early 1800s they have long since lost the ability to perform magic. They can only write long, dull papers about it, while fairy servants are nothing but a fading memory.

MY THOUGHTS:

People say that every new author needs a fresh voice. Clarke surely has one, but part of her uniqueness comes from closely copying long gone masters of the Victorian genre, as contradictory as that sounds. She has Jane Austen's witty conversations and wise social satire down pat. And she's also nailed Charles Dickens' enormous community scope and wide range of characters. It's a bit like reading either one of those two, but on top of that, there's amazing fantasy!

Clarke presents England in the Napoleonic Wars just as it was, with appearances from the Duke of Wellington, Lord Byron and mad King George III. But history gets an alternative twist with the addition of two magicians who are highly valued contributors to the war effort. They are both trying hard to raise the public profile of magic so it's on a par with the army, church or politics as a potential occupation.

Mr Gilbert Norrell is a pedantic old scholar who's addicted to hoarding knowledge, because he can't trust others to wield such a powerful tool. In reality he's a control freak with a compulsion to stay on top of what's going on. For years his main hobby has been buying valuable, out-of-print books of magic to hide in his own personal library so nobody else can read them.

Jonathan Strange is a capricious and impulsive young man who's always found it hard to settle down to anything, but discovers a sudden genius for magic which impresses Norrell as the real deal. Norrell offers to be his tutor so he can control Strange's talent and direct it to suitable channels.

Their utterly different learning styles really appealed to my homeschooling heart. Norrell considers a decade of study to be merely scratching the surface, while Strange whips off articles the night before they're due. Norrell wants to wrap his intellect around the ins and outs of everything, while Strange isn't afraid to follow his instincts and see what happens. Norrell is careful to handle with kid gloves things he only partially understands, while Strange longs to dive right in for the same reason. The discord makes an excellent read, especially since Strange knows very well that there are thousands of books Norrell is withholding from him, choosing to keep a tight rein over the nuggets of knowledge he chooses to dispense.

There are strong dangers of dabbling around in the murky supernatural. Even though Strange and Norrell are devoted fanatics, they unleash perils of which they are both oblivious and almost destroy the lives of certain other characters. This is particularly true when it comes to enlisting the help of the fairy kingdom.

People are fascinated with elusive fairies and the possibility of winning their favour or servitude. Yet fairies prove to be a malicious and loathsome race, devoid of human empathy. Especially one manipulative character who is mostly referred to as 'the gentleman with the thistledown hair.' Totally self-interested and calculating, he reminds me of folklore villains like Rumplestiltskin, with his, 'What's in it for me?' attitude. We have to find out whether Strange and Norrell can eventually foil him, since they've no idea what's going on beneath their own noses. He's so much more cluey than either of them in many ways, it would seem that if they do, it'd have to be by accident. I found this guy really nasty, but also sort of cool.

People are fascinated with elusive fairies and the possibility of winning their favour or servitude. Yet fairies prove to be a malicious and loathsome race, devoid of human empathy. Especially one manipulative character who is mostly referred to as 'the gentleman with the thistledown hair.' Totally self-interested and calculating, he reminds me of folklore villains like Rumplestiltskin, with his, 'What's in it for me?' attitude. We have to find out whether Strange and Norrell can eventually foil him, since they've no idea what's going on beneath their own noses. He's so much more cluey than either of them in many ways, it would seem that if they do, it'd have to be by accident. I found this guy really nasty, but also sort of cool.Anyone who attempts to read the book will quickly discover its main quirk, which is all the footnotes! They basically tell the history of English magic from the world Susanna Clarke has made up especially for this novel. Sure, they distract from the flow of the story, but you can't possibly skip them without sacrificing what's so precious to Strange and Norrell, including the hazy, centuries old legends about John Uskglass, an ancient magician and monarch known as The Raven King. Some of them are weird and whacky enough to make novels of their own. So much ingenuity has gone into them, if you love the book you've got to love the footnotes. (Although I admit my heart sometimes failed me when I turned a page and saw the size of one to come.)

My final verdict is that it's dense, brain-bending and long enough, at almost 900 pages, to feel we've been sucked into Faerie ourselves, and wonder when we'll emerge. There are dazzling enchantments and many episodes as circuitous as the passages to Norrell's library which turn out to be mainly scene setters, or to keep the tantalising real action at bay. But all this makes it the sort of book we can be proud of ourselves for finishing. On the whole it's rewarding enough to make up for its brick-like quality, since there are at least a couple of things to grin at on every page. When you add them all together, that's a lot of smiles :)

And I'll finish off with some quotes from my new favourite, Jonathan Strange.

Lord Wellington: Can a magician kill a man by magic?

Strange: I suppose a magician might. But a gentleman could not.

Jonathan Strange (to the king): Though Great Britain may desert us, we have no right to desert Great Britain. She may have need of us yet.

Also, see this reflection about Enchantments and Depression.

🌟🌟🌟🌟🌟